What Are Brain-Computer Interfaces?

The brain-computer interface (BCI) is a revolutionary advancement bridging technology and translational neuroscience. BCIs can be used to develop more advanced prosthetics for a variety of different conditions. We typically think of prosthetics as replacing lost limbs, but in reality, prosthetics can restore a variety of senses and even add to otherwise normal human capabilities. For example, a visual neuroprosthesis could restore sight in individuals with certain types of blindness by bypassing the cause of their visual deficits. Researchers have already begun investigating the potential of using our neural potential to control extra limbs (Farina et al., 2023) or exoskeletons! Furthermore, we can use BCIs to monitor and treat mental health and other types of medical conditions, such as using targeted electrical stimulation to improve fatigue and burnout.

But how do these BCIs work?

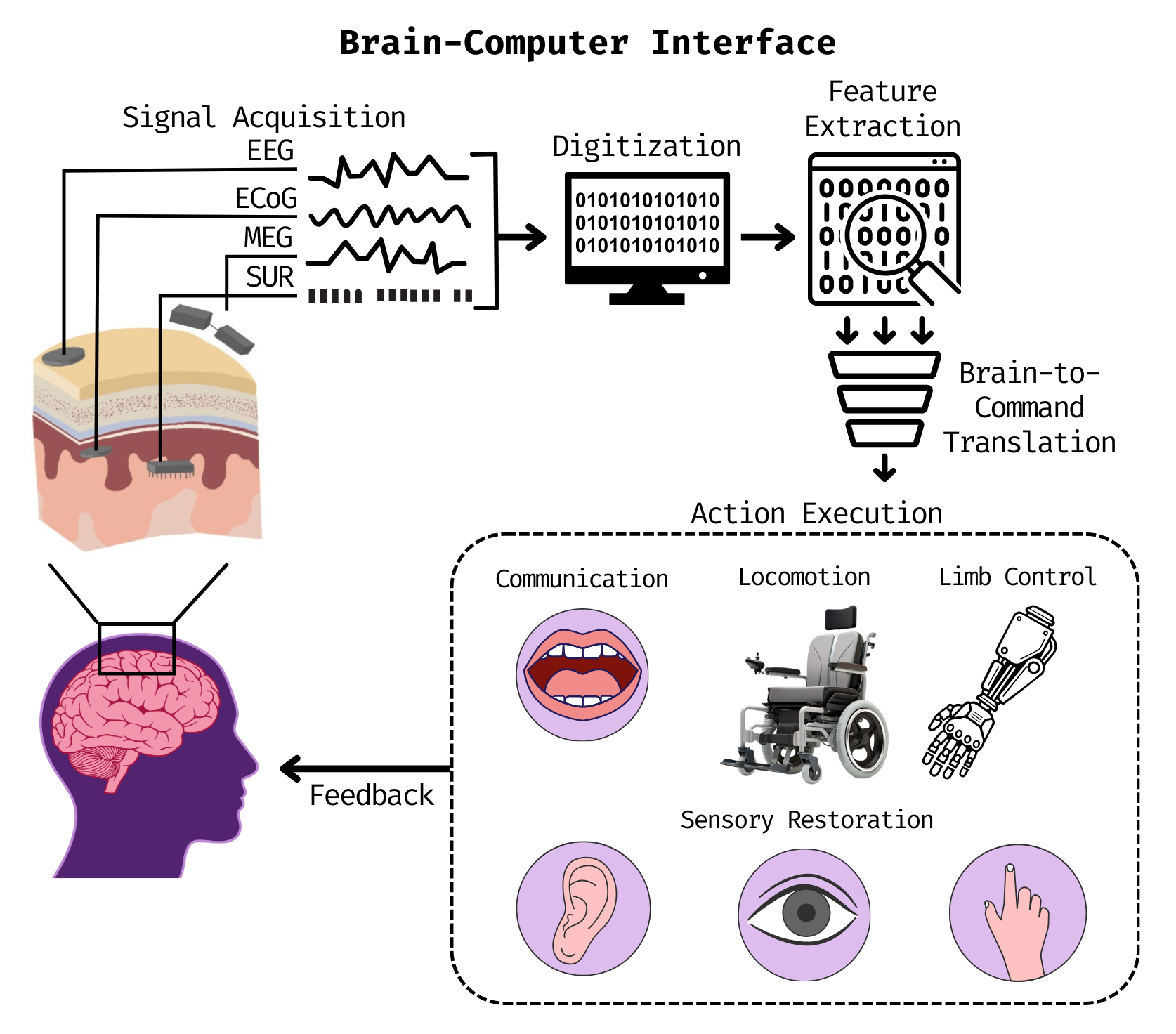

BCIs capture neural activity from central nervous system signals, analyze the features and patterns within these signals, translate these features into commands, and send those demands to a device to trigger an action. Let’s break this down further.

Capture neural activity

There are many ways to capture neural activity for a BCI, but these can generally be divided into two subtypes: invasive and non-invasive. Invasive methods are used more than non-invasive methods for BCIs, but research is moving towards non-invasive methods to expand the BCI user pool.

Invasive Methods

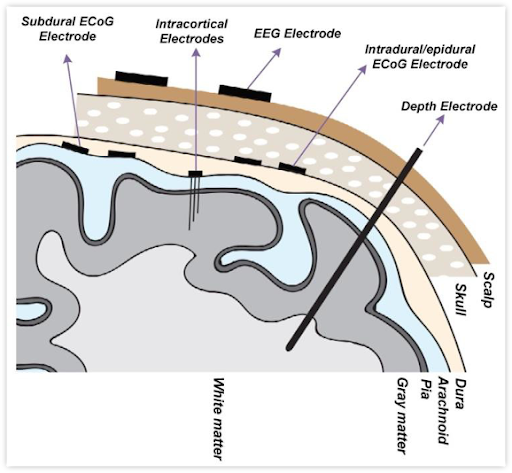

(Image from Ranjandish et al., 2020)

The invasive types of neural recording techniques include single-unit recording (SUR) and electrocorticography (ECoG). SUR uses microelectrodes implanted into the brain to capture electrical activity, called spikes, from individual neurons. This is like sticking a single hair deep into the brain. ECoG, on the other hand, uses grids of electrodes implanted on the surface of the brain to record activity from a small group of neurons. There are many more electrodes used for ECoG compared to SUR, but SUR goes much deeper into the brain. This means that SUR has a higher spatial resolution than ECoG. Both of these methods have high temporal resolution because they directly measure the fast (ms) electrical changes from neurons. These methods provide high-quality signals because we can directly record from the brain tissue. This is measured as a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which is the amount of desired neural signal compared to the amount of background noise. Invasive methods have much higher SNRs than non-invasive methods because they record from the tissue directly!

Non-Invasive Methods

There are many more types of non-invasive techniques, including functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), electroencephalography (EEG), and magnetoencephalography (MEG). These methods can capture whole-brain neural activity, while invasive methods can only capture activity from a small section of neurons. fMRI uses a large tube filled with strong magnets to map neural activity by detecting changes in blood flow and the amount of oxygenated blood in different regions of the brain. fMRI is not used as much as the other two methods because it has a relatively low temporal resolution (blood moves much more slowly than electricity!), despite having greater spatial resolution than both of them. EEG uses caps of electrodes placed on the scalp or many loose electrodes temporarily glued to the scalp to record electrical activity from the whole brain. The signal has to travel through the skull and scalp to get to the electrodes, so it has a lower SNR than invasive methods. MEG is a cousin of EEG, which uses a large hood of sensors around the head to record the magnetic fields generated by electrical activity from the whole brain. MEG has higher temporal resolution than both fMRI and EEG, as well as similar temporal resolution and SNR to EEG.

If you are interested in learning more about any of these techniques, I have started a series of posts dedicated to explaining how each modality works!

The Tasks

No matter the method of recording, BCIs capture neural activity during specific tasks aiming to generate patterns of activity that are relevant to the desired output. For example, someone using a BCI-controlled prosthetic arm would engage in tasks where they imagine moving the arm in specific ways. The imagining will generate neural signals that have features and patterns for the BCI to learn, so that it can send commands to the prosthetic arm. This type of task is called motor imagery, which I have described in a previous post. Other types of BCIs use signals generated by visual or auditory processing, called evoked potentials. Using visual evoked potentials can allow users to play video games, type, etc. Research is also trying to use auditory evoked potentials to reconstruct heard speech!

Although this is not an exhaustive list, hopefully, this gives you a feel for how the neural signals for BCI control are generated.

Feature Extraction and Translation

BCIs capture and quantify the features of neural signals that indicate what the user is intending to do. This means separating the signal features that are related to the intended action from the background noise/other features.

Note that the relevant brain activity is typically oscillatory, meaning that we want to capture information about the brain waves associated with the user’s intentions. As I described in a previous post, brain waves can vary in speed (frequency) and strength (amplitude), forming different frequency bands, where each band has a characteristic pattern. The frequency bands we typically refer to are delta, theta, alpha, beta, and gamma bands, with gamma being the highest-frequency band and delta being the lowest-frequency band. For a neural signal, we can also measure the amount of energy there is in different frequency bands, called the power within these bands. For methods like ECoG, EEG, and MEG, the most common features for current BCIs are the amplitudes of the signal and the power in different frequency bands. For SUR, the most common features are the firing rates of individual neurons, which can be measured by the number of spikes in a certain amount of time.

Once the relevant features are extracted, they are passed to a computational model that converts the features into commands that aim to perform the intended action. Currently, BCIs use artificial intelligence-based models for this purpose because they can learn patterns from the set of features.

Examples of BCIs

Paradromics’ Connexus

Paradromics develops BCIs to translate brain activity into speech, text, and cursor control for people with severe motor impairments. The Connexus uses 420 micro-electrodes implanted in the temporal lobe of the brain, which is a key region for auditory processing. Although not yet FDA-approved, Paradromics successfully completed its first implantation in 2025!

Neurable’s BCI Headphones

Neurable integrates BCI technology into everyday devices, such as headphones, to improve focus and prevent burnout. The BCI headphones use EEG brain tracking with sophisticated data analysis and signal processing methods to maximize the user’s focus time throughout the day. It also allows users to track their cognition over time.

Inbrain Nanoelectronics’ Graphene Chip

Inbrain Nanoelectronics is working to restore mobility in those with disabilities and develop neuroelectronic therapies. The graphene chip tracks and stimulates neural activity, which may eventually help treat conditions like Parkinson’s disease by determining and tracking how well the patient’s medications are working. This is important, as patients develop resistance to the medications they are on, forcing doctors to change their medications over time to keep up.

Synchron’s Stentrode

Synchron aims to use blood vessels to map the brain. The Stentrode is inserted into the body via the jugular vein and implanted in a region near the motor cortex of the brain, called the superior sagittal sinus. The user also has a receiver implanted into their chest, to which the chip transmits neural signals. The receiver translates the neural data into keystrokes and clicks, allowing the user to control a computer. This helps people with severe motor impairments communicate and interact with digital environments!

Neuralink’s Link

Neuralink aims to restore autonomy to individuals with disabilities through a variety of clinical BCI trials. The Link uses multiple hair-like electrodes implanted deep in the brain to enable individuals with quadriplegia to control a variety of external devices, from computers to wheelchairs to bionic arms. As of February 2025, Neuralink has successfully implanted the Link into three patients.

BCI technology is a groundbreaking field that can improve the lives of millions of people by using the power of the mind to bypass the limitations of the body. What do you think about BCIs? Leave a comment!

-

Farina, D., Burdet, E., Mehring, C., Ibáñez, J. (2023). Roboticists Want to Give You a Third Arm. IEEE Spectrum. spectrum.ieee.org/human-augmentation.

Ranjandish, R., & Schmid, A. (2020). A Review of Microelectronic Systems and Circuit Techniques for Electrical Neural Recording Aimed at Closed-Loop Epilepsy Control. Sensors, 20(19), 5716. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20195716

Un-cited image components developed in Canva.