With Movement in Mind: How Imagination Strengthens Us

“Mind over matter” is a phrase I’m sure most of us have heard before. We are taught from a young age that it takes hard work to be successful, but there are many different ways in which that hard work can manifest itself. For example, many people suffer from age-related motor deficits, spinal cord injuries, car accidents, and sports-related accidents each year. These circumstances often require physical therapy and rehabilitation to help those affected begin to move like they used to.

In recent years, researchers in neuroscience and physical therapy have shown the potential of a new type of therapy that could make rehabilitation easier for all, especially older adults. This is motor imagery.

What is Motor Imagery?

Motor imagery is described as the “conscious access to the content of the intention of a movement” (Jeannerod, 1995). In other words, motor imagery happens when you intentionally imagine or think about moving some part of your body. For instance, closing your eyes and imagining lifting your foot off the ground without actually doing it is an instance of motor imagery.

Motor imagery generates neural signals that are too weak to actually cause muscle movement, but are strong enough to make an impact in other ways.

What Does Motor Imagery Have to Do With Physical Therapy?

Researchers have found that motor imagery affects the nervous system and muscle excitability, which is the ability of the nervous system to activate muscles. Research suggests that motor imagery training across multiple sessions increases excitability of the main muscles responsible for motor imagery-targeted movements through the corticospinal tract (the brain's main pathway for voluntary movement), particularly when combined with electrical stimulation of the target muscles, which helps strengthen neural pathways in the brain and spinal cord.

There are several functional improvements measured from motor imagery training with and without additional stimulation:

Strength and Dexterity Improvements

In healthy adults, motor imagery training increases the maximum strength and strength development of foot flexors (Grosprêtre et al., 2018). Meanwhile, in people with cervical spinal cord injuries, motor imagery training sessions with and without spinal cord stimulation improved manual dexterity, the skill and quickness in performing tasks with hands (Capozio et al., 2025).

Mobility and Rehabilitation Improvements

Motor imagery training improves balance, walking speed, and performance on the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test (see below) in older healthy adults (Nicholson et al., 2019). In patients recovering from total hip replacements, combining motor imagery training with action observation training, in which participants watch videos or live actions performed by someone else, improved walking speed and TUG test performance, improved the consistency of foot in-air time between steps (swing-time variability), and improved cognitive performance during multi-tasking while walking/balancing (Marusic et al., 2018).

-

The TUG test is a common clinical assessment that measures mobility, balance, and fall risk by timing how long it takes someone to stand from a chair, walk 3 meters, turn, walk back, and sit down.

Excitability of the Corticospinal Tract

We can measure the impact of motor imagery on the nervous system pathways responsible for movement through motor-evoked potentials, or MEPs. MEPs are electrical signals that we can record from the motor pathways moving from the brain to the spinal cord to the muscles, or from the muscles resulting from stimulation of these motor pathways (Legatt, 2014).

In both healthy people and people with cervical spinal cord injuries, motor imagery training with and without spinal cord stimulation increases the excitability of the corticospinal tract (see below), shown through increased MEPs, while stimulation alone does not (Capozio et al., 2025; Takahashi et al., 2019).

-

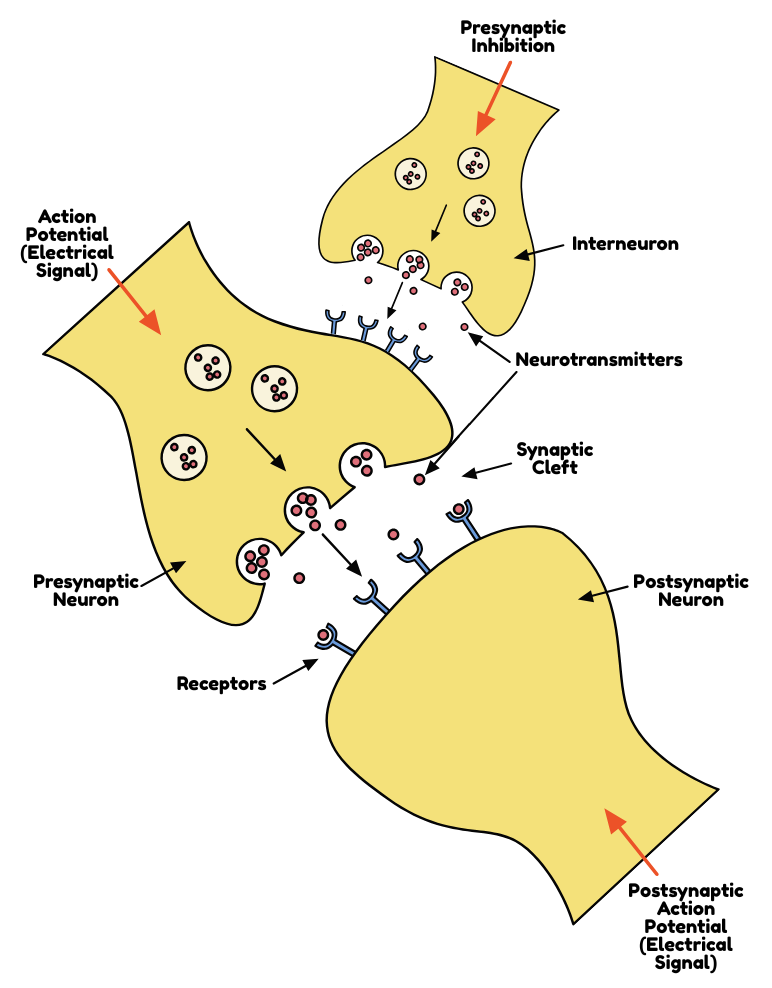

The corticospinal tract is the brain's main pathway for voluntary movement. It connects the cerebral cortex to the spinal cord, which controls muscles in the limbs and torso. The neurons that travel in this tract are called upper motor neurons, which connect to neurons in the spinal cord called lower motor neurons through synapses.

You can learn more about the corticospinal tract in this lovely article from Physiopedia.

Use-Dependent Plasticity

Use-dependent plasticity is the brain's ability to change its motor map (in the primary motor cortex) based on repeated actions to strengthen pathways for frequently used movements.

In addition to MEPs, we can measure changes in motor-related nervous system pathways above the level of the spinal cord (supraspinal) and use-dependent plasticity through volitional (V)-waves (see below) and electromyography, which records the electrical activities of muscles through electrodes attached to the skin.

Researchers have found that motor imagery training improves strength, and this training results in higher V-wave amplitude and electromyographic activity--both of which indicate that supraspinal motor control is increased (Grosprêtre et al., 2018).

Additionally, after motor imagery training with a specific target direction in mind, transcranial magnetic stimulation-induced movements deviate toward the trained direction, indicating use-dependent plasticity (Ruffino et al., 2019).

-

A V-wave is a spinal reflex that results from strong voluntary muscle activity using electrical stimulation strong enough to activate all the fibers of a nerve. The electrical stimulation sends signals both toward the muscle and back toward the spinal cord. At the same time, the brain sends strong descending signals down the corticospinal tract to the nerve cells that directly control skeletal muscle contractions, called alpha motor neurons. These two signals are travelling in opposite directions, so they collide and the signals coming from the brain cancel the other signals out. The V-wave is proportional to the amount of descending neural commands from the brain (Grosprêtre et al., 2018).

Excitability of Spinal Motor Neurons

We can measure spinal excitability through F-waves and the H-reflex. The H-reflex is a spinal reflex arc that involves both sensory fibers and motor neurons, while the F-wave is a late muscle response from the activation of motor neurons by electrical stimulation. Essentially, the electrical stimulus travels backward toward the spinal cord, and if a motor neuron "backfires" after stimulation, an electrical signal travels forward toward the muscle to cause a muscle contraction, measured as an F-wave.

At the spinal level, motor imagery increases spinal motor neuron excitability regardless of the imagined muscle contraction strength. Without training, this is time-dependent, meaning that the increases in excitability return to baseline quickly (within ~5 minutes) (Bunno et al., 2017).

However, after intense, slightly longer (20 minutes) sessions, researchers have found that motor imagery facilitates increased heteronymous facilitation, which is when the excitability/strength of a reflex in one muscle increases due to the stimulation of sensory nerves from a different, related muscle (Manning & Bawa, 2011; Grosprêtre et al., 2019). Motor imagery, in this case, also impacts something called presynaptic inhibition.

Typically, there is a baseline level of presynaptic inhibition in the spinal cord that filters sensory inputs to prevent them from over-exciting motor neurons, which is mediated by cells called interneurons. Motor imagery generates neural signals that are too weak to actually cause muscle movement, but are strong enough to activate these interneurons, which inhibits them (reduces their mediation of the presynaptic inhibition in the spinal cord). This essentially cancels that baseline presynaptic activity (Grosprêtre et al., 2018). We can see this through an increase in H-reflex amplitude.

Furthermore, with training, motor imagery increases spinal motor neuron excitability that correlates with strength gains (Grosprêtre et al., 2018). When paired with electrical stimulation, motor imagery also increases reciprocal inhibition, which is a spinal inhibitory mechanism where contracting a muscle causes the opposing muscle to relax (Takahashi et al., 2019). For example, to bend your elbow, your bicep contracts while your tricep relaxes.

Why Should We Care?

These results suggest that, during motor imagery training, the brain prepares the spinal cord and motor pathways for potential movement by removing inhibitory "brakes".

But what’s the point?

Imagine you are an athlete who hurt your ankle and now you have to wear a cast. You can use motor imagery training to maintain neuromuscular function while you can't use your ankle. Or perhaps you have gotten in a car accident and have a cervical spinal cord injury. You can use motor imagery training with or without spinal cord stimulation to improve your corticospinal tract excitability. Or maybe you are recovering from a hip replacement and have to go through post-surgical physical therapy. You can use motor imagery training with action observation to further improve your functional mobility and walking speed.

Overall, motor imagery training is a pain-free, cost-free approach to improving mobility when movement is limited!

-

Bunno, Y., Fukumoto, Y., Marina, T., Onigata, C. (2017), The Effect of Motor Imagery on Spinal Motor Neuron Excitability and Its Clinical Use in Physical Therapy, Neurological Physical Therapy. http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/67471

Capozio, A., Graham, M., Ichiyama, R., Astill, S.L. (2025), A single session of motor imagery paired with spinal stimulation improves manual dexterity and increases cortical excitability after spinal cord injury, Clinical Neurophysiology, 174: 160-168.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2025.03.047

Grosprêtre, S., Jacquet, T., Lebon, F., Papaxanthis, C. and Martin, A. (2018), Neural mechanisms of strength increase after one-week motor imagery training. European Journal of Sport Science, 18: 209-218. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2017.1415377

Grosprêtre, S., Lebon, F., Papaxanthis, C. and Martin, A. (2019), Spinal plasticity with motor imagery practice. J Physiol, 597: 921-934. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP276694

Jeannerod, M. (1995), Mental imagery in the motor context. Neuropsychologia, 33(11): 1419-1432. https://doi.org/10.1016/0028-3932(95)00073-C

Legatt, A.D. (2014), Motor Evoked Potentials. Encyclopedia of the Neurological Sciences, 111-114. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-385157-4.01109-X

Manning, C.D. & Bawa, P. (2011), Heteronymous reflex connections in human upper limb muscles in response to stretch of forearm muscles. Journal of Neurophysiology, 106:3, 1489-1499. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00084.2011

Marusic, U., Grosprêtre, S., Paravlic, A., Kovač, S., Pišot, R., Taube, W. (2019), Motor Imagery during Action Observation of Locomotor Tasks Improves Rehabilitation Outcome in Older Adults after Total Hip Arthroplasty, Neural Plasticity. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/5651391

Nicholson, V., Watts, N., Chani, Y., Keogh J.W.L. (2019), Motor imagery training improves balance and mobility outcomes in older adults: a systematic review, Journal of Physiotherapy, 65(4): 200-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2019.08.007.

Physiopedia contributors (2025), Corticospinal Tract, Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/index.php?title=Corticospinal_Tract&oldid=368897

Ruffino, C., Gaveau, J., Papaxanthis, C., Lebon, F. (2019), An acute session of motor imagery training induces use-dependent plasticity, Scientific Reports, 9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-56628-z

Takahashi, Y., Kawakami, M., Yamaguchi, T., Idogawa, Y., Tanabe, S., Kondo, K., Liu, M. (2019), Effects of Leg Motor Imagery Combined With Electrical Stimulation on Plasticity of Corticospinal Excitability and Spinal Reciprocal Inhibition, Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.00149

Image components developed in Canva.