Baby Talk: A Breakdown of “Prenatal Experience with Language Shapes the Brain”

Whenever I’m around babies and other young children, I am always amazed at how we can learn to speak our native language fluently with little effort, despite speaking gibberish for most of our first few years. I’m even more amazed at this when I try to learn new languages as an adult, with much struggling and little success. According to research by Benedetta Mariani and colleagues (2023), native language learning actually starts in the womb, giving us a head start that we don’t have when learning languages as adults! In today’s installment of Brain on the Bayou, I’ll detail what Mariani et al. (2023) found and how they did it.

In this study, Mariani et al. (2023) aimed to investigate the neural processes that give human babies the ability to learn language quickly and efficiently. Specifically, they ask two main questions:

Does exposure to language cause lasting changes in the newborn brain and its processes (neural plasticity) that support learning and memory?

Are these changes specific to language experience before birth?

The researchers hypothesized that newborn babies should show greater neural activity changes after being exposed to their native language compared to other languages if experience with language in the womb shapes the brain.

But why do they think this?

Their reasoning comes down to how the environment inside the uterus filters sound and how the brain processes speech:

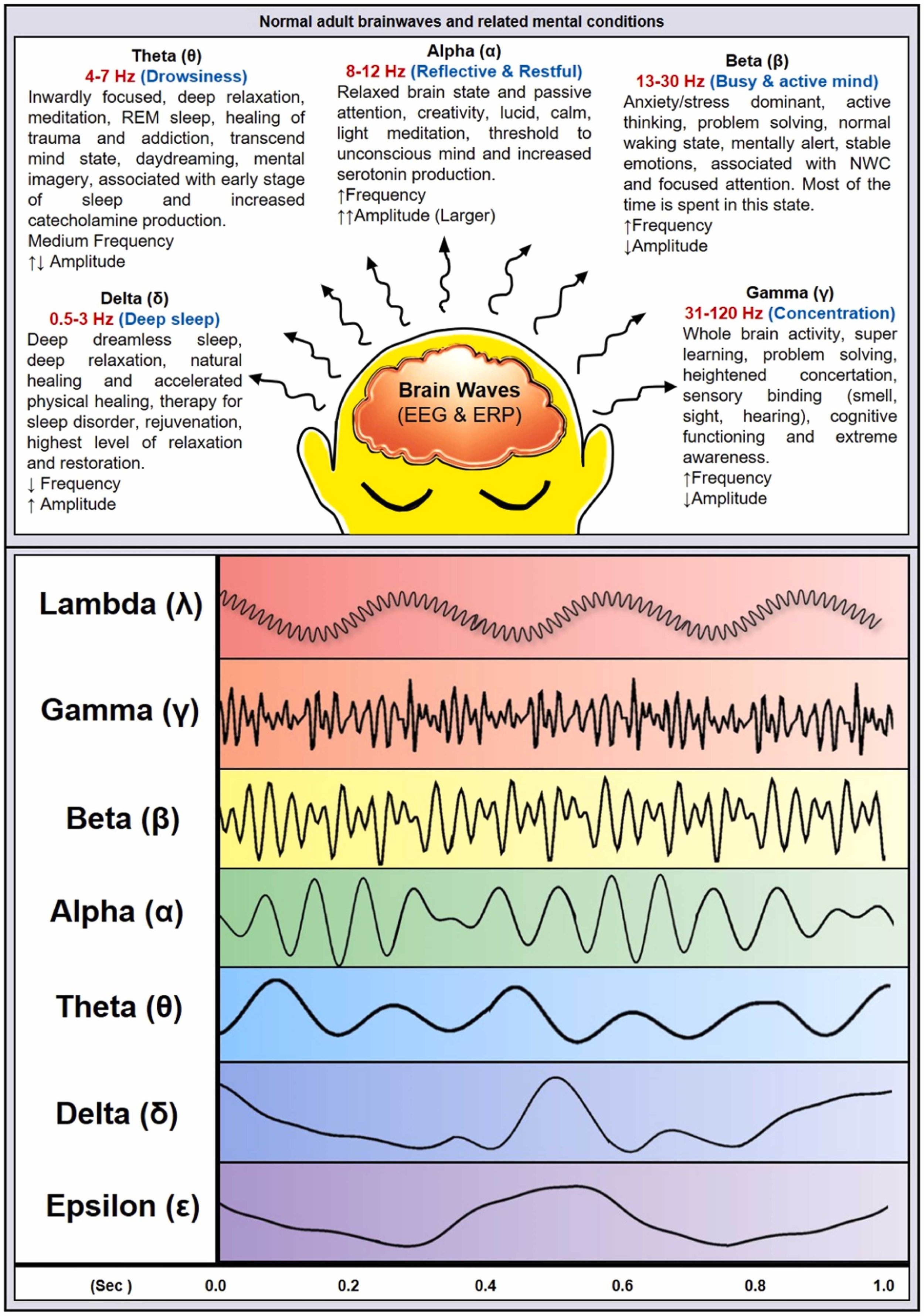

Image by Sahu et al., 2024. Ageing Research Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2024.102547

The environment inside the uterus acts like a low-pass filter, meaning that it blocks high-frequency sounds. This means that fetuses are mainly exposed to melody and rhythm, rather than phonemes, which are individual speech sounds (i.e., the b sound in brother). Think of this like listening to someone with your head underwater; you can hear how the person is talking, but can’t make out exactly what they are saying.

Neurons in the brain generate electrical signals. When neurons generate these signals in sync with each other, the signals form a pattern or rhythm called a neural oscillation or a brainwave. These rhythms can vary in speed (frequency) and strength (amplitude), forming different frequency bands, where each band has a characteristic pattern. The frequency bands we typically refer to are delta, theta, alpha, beta, and gamma bands, with gamma being the highest-frequency band and delta being the lowest-frequency band.

When the brain processes speech, specific frequency bands are associated with processing different aspects of language. Mariani et al. (2023) focus on theta and gamma bands, where the theta band is associated with syllable processing and the gamma band is associated with the processing of phonemes. The researchers predicted that language learning in the womb targets theta oscillations instead of gamma oscillations because of the low-pass filtering of sound in the uterus.

Mariani et al. (2023) predict that, as a newborn, experiencing the language that they “learned” in the womb triggers the previously experienced language processing state of the brain, leading to an increase in something called Long-Range Temporal Correlations (LRTCs).

LRTCs are patterns in brain activity that show how past events influence future events over a long span of time. We can see if there is an increase in LRTCs by doing a Detrended Fluctuation Analysis (DFA). DFA is a method for determining if and how events that are far apart in space or time stay related to each other. DFA has an exponent 𝛼 that we can use to see how strong the LRTCs are. If 𝛼 is higher, there is an increase in LRTCs.

Now that we know what they are looking for, how do they actually measure this in babies?

The researchers did three EEG experiments with 33 native French newborns:

In the Silence 1 condition, they recorded the babies resting for three minutes.

In the Language Experience condition, they exposed the babies to three 7-minute chunks of speech in different languages (French, Spanish, and English). The newborn babies experience French in the womb, but not Spanish or English. Spanish has a similar rhythm to French and English does not (Keep in mind what I said before about processing rhythms!).

In the Silence 2 condition, they recorded the babies resting again for three minutes.

They applied DFA and looked at the changes in neural processes from the Silence 1 condition to the Silence 2 condition.

So, what did they find?

No matter what the language is, there was a significant increase in LRTCs (higher 𝛼) for theta oscillations when comparing Silence 1 to Silence 2. This supports the idea that exposure to language strengthens long-range correlations in the brain at the syllable level.

For gamma oscillations, there was a decrease in LRTCs, supporting the idea that the brain changes were specific to frequencies experienced in the womb (phonemes aren’t heard in the womb, so gamma oscillations don’t play a big role until birth!).

When the researchers separated newborns by the last language they heard, only those exposed to French (their native language) last showed significant increases in LRTCs for theta oscillations. This indicates that there is a specific effect of the native language.

Overall, this study by Mariani et al. (2023) supports the understanding that experience with language in the womb helps shape the functional organization of the brain before birth. Contrary to what some might believe, babies are not “blank slates”, but are primed for learning from square one!

What do you think about these findings? Comment below!

-

Mariani, B., Nicoletti, G., Barzon, G., Barajas, M.C.O., Shukla, M., Guevara, R., Suweis, S.S., Gervain, J. (2023), Prenatal experience with language shapes the brain, Science Advances, 9(47). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adj3524

Sahu, M., Ambasta, R.K., Das, S.R., Mishra, M.K., Shanker, A., Kumar, P. (2024), Harnessing Brainwave Entrainment: A Non-invasive Strategy To Alleviate Neurological Disorder Symptoms, Ageing Research Reviews, 101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2024.102547

Image components developed in Canva.